Participatory democracy

This article possibly contains synthesis of material which does not verifiably mention or relate to the main topic. (July 2023) |

| Part of the Politics series |

| Democracy |

|---|

|

|

Participatory democracy, participant democracy, participative democracy, or semi-direct democracy is a form of government in which citizens participate individually and directly in political decisions and policies that affect their lives, rather than through elected representatives.[1] Elements of direct and representative democracy are combined in this model.[2]

Overview

[edit]Participatory democracy is a type of democracy, which is itself a form of government. The term "democracy" is derived from the Greek expression δημοκρατία (dēmokratia) (δῆμος/dēmos: people, Κράτος/kratos: rule).[3] It has two main subtypes, direct and representative democracy. In the former, the people have the authority to deliberate and decide legislation; in the latter, they choose governing officials to do so. While direct democracy was the original concept, its representative version is the most widespread today.[4]

Public participation, in this context, is the inclusion of the public in the activities of a polity. It can be any process that directly engages the public in decision-making and gives consideration to its input.[5] The extent to which political participation should be considered necessary or appropriate is under debate in political philosophy.[6]

Joining political parties allows citizens to participate in democratic systems, but is not considered participatory democracy.

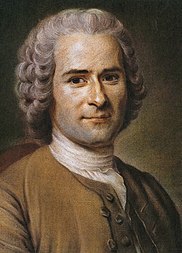

Participatory democracy is primarily concerned with ensuring that citizens have the opportunity to be involved in decision-making on matters that affect their lives.[6] It is not a new concept and has existed in various forms since the Athenian democracy. Its modern theory was developed by Jean-Jacques Rousseau in the 18th century and later promoted by John Stuart Mill and G. D. H. Cole, who argued that political participation is indispensable for a just society.[7] In the early 21st century, participatory democracy has been more widely studied and experimented with, leading to various institutional reform ideas such as participatory budgeting.[8]

History

[edit]Origins in Ancient Greece

[edit]Democracy in general first appeared in the city-state of Athens during classical antiquity.[9][10] It was first established under Cleisthenes in 508–507 BC.[11] This was a direct democracy, in which ordinary citizens were randomly selected to fill government administrative and judicial offices, and there was a legislative assembly consisting of all Athenian citizens.[12] However, Athenian citizenship excluded women, slaves, foreigners (μέτοικοι/métoikoi) and youths below the age of military service.[13][14] Athenian democracy was the most direct in history as the people controlled the entire political process through the assembly, the boule and the courts, and a large proportion of citizens were involved constantly in public matters.[10]

During the 20th century

[edit]During the 20th century, practical implementations began to take place, mostly on a small scale, attracting considerable academic attention in the 1980s. Experiments in participatory democracy took place in various cities around the world. As one of the earliest examples, Porto Alegre, Brazil adapted a system of participatory budgeting in 1989. A World Bank study found that participatory democracy in these cities seemed to result in considerable improvement in the quality of life for residents.[15]

In the 21st century

[edit]In the early 21st century, experiments in participatory democracy began to spread throughout South and North America, China, and across the European Union.[16] In a US example, the plans to rebuild New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina in 2005 were drafted and approved by thousands of ordinary citizens.[15]

The Citizens' Assembly (2011) in Ireland

[edit]In 2011, as a response to citizens' growing distrust in the government following the financial crisis of 2007–2008, Ireland authorised a citizens' assembly called "We the Citizens". Its task was to pilot the use of a participatory democratic body and test whether it could increase political legitimacy. There was an increase in both efficacy and interest in governmental functions, as well as significant opinion shifts on contested issues like taxation.[17]

The Citizens Convention for Climate in France (2019)

[edit]The French government organised "le grand débat national" (the Great National Debate) in early 2019 as a response to the Yellow vests movement. It consisted of 18 regional conventions, each with 100 randomly selected citizens, that had to deliberate on issues they valued the most so that they could influence government action.[18] After the debate, a citizens' convention was created specifically to discuss climate change, "la Convention citoyenne pour le climat" (the Citizens Convention for Climate, CCC), designed to serve as a legislative body to decide how the country could reduce its greenhouse gas emissions with social justice in mind.[19] It consisted of 150 citizens selected by sortition and stratified sampling, who were sorted into five sub-groups to discuss individual topics. The members were helped by experts on steering committees. The proceedings of the CCC garnered international attention. After nine months, the convention outlined 149 measures in a 460-page report, and President Macron committed to supporting 146 of them. A bill containing these was submitted to the parliament in late 2020.[18]

Effects of social media

[edit]In recent years, social media has led to changes in the conduct of participatory democracy. Citizens with differing points of view are able to join conversations, mainly through the use of hashtags.[20] To promote public interest and involvement, local governments have started using social media to make decisions based on public feedback.[21] Users have also organised online committees to highlight local needs and appoint budget delegates who work with the citizens and city agencies.[22]

The Occupy movement

[edit]Participatory democracy was a notable feature of the Occupy movement in 2011. "Occupy camps" around the world made decisions based on the outcome of working groups where every protester had a say. These decisions were then aggregated by general assemblies. This process combined equality, mass participation, and deliberation.[23]

Evaluation

[edit]Strengths

[edit]

The most prominent argument for participatory democracy is its function of greater democratization.

[T]he argument is about changes that will make our own social and political life more democratic, that will provide opportunities for individuals to participate in decision-making in their everyday lives as well as in the wider political system. It is about democratizing democracy.

— Carole Pateman, Participatory Democracy Revisited, Perspectives on Politics. 10 (1): 7–19, 2012

With participatory democracy, individuals or groups can realistically achieve their interests, "[providing] the means to a more just and rewarding society, not a strategy for preserving the status quo."[7]

Participatory democracy may also have an educational effect. Greater political participation can lead to the public to seeking to also make it higher quality in efficacy and depth: "the more individuals participate the better able they become to do so",[7] an idea already promoted by Rousseau, Mill, and Cole.[8] Pateman emphasises this potential as it counteracts the widespread lack of faith in the capacity and capability of citizens to meaningfully participate, especially in societies with complex organisations.[8] Joel D. Wolfe asserts his confidence that such models could be implemented even in large organizations, progressively diminishing state intervention.[7]

Criticism

[edit]Criticisms of participatory democracy generally align with criticism of democracy.[citation needed] The main opposition is the disbelief in citizens' capabilities to bear the greater responsibility. Some reject the feasibility of participatory models and refutes its proposed educational benefits.

First, the self-interested, rational member has little incentive to participate because he lacks the skills and knowledge to be effective, making it cost-effective to rely on officials' expertise.[24]

Critics conclude that the citizenry is disinterested and leader-dependent, making the mechanism for participatory democracy inherently incompatible with advanced societies.

Other concerns are whether such massive political input can be managed and turned into effective output. David Plotke[who?] highlights that the institutional adjustments needed to make greater political participation possible would require a representative element. Consequently, both direct and participatory democracy must rely on some type of representation to sustain a stable system. He also states that achieving equal direct participation in large and heavily populated regions is hardly possible, and ultimately argues in favor of representation over participation, calling for a hybrid between participatory and representative models.[25]

A third category of criticism, primarily advanced by author Roslyn Fuller, rejects equating or even subsuming instruments of Deliberative Democracy (such as citizens’ assemblies) under the term of Participatory Democracy, as such instruments violate the hard-won concept of political equality (One Man, One Vote), in exchange for a small chance of being randomly selected to participate and are thus not ‘participatory’ in any meaningful sense.[26][27]

Proponents of Deliberative Democracy in her view misconstrue the role sortition played in the ancient Athenian democracy (where random selection was limited only to offices and positions with very limited power whereas participation in the main decision-making forum was open to all citizens).[28][29]

Fuller's most serious criticism is that Deliberative Democracy purposefully limits decisions to small, externally controllable groups while ignoring the plethora of e-democracy tools available which allow for unfiltered mass participation and deliberation.[26][30]

Business philosopher Jason Brennan advocates in book Against Democracy for a less participatory system because of the irrationality of voters in a representative democracy. He proposes several mechanisms to reduce participation, presented with the assumption that a vote-based system of electoral representation is maintained.[31] Comparing an untested voter to an unlicensed driver, Brennan argues that exams should be administered to all citizens to determine if they are competent to participate in public matters. Under this system, citizens either have one or zero votes, depending on their test performance. Critics of Brennan, including reporter Sean Illing, found parallels between his proposed system and the literacy tests the Jim Crow laws that prevented black people from voting in the United States between.[32] Brennan proposes a second system in which all citizens have equal rights to vote or otherwise participate in government, but decisions made by the elected representatives are scrutinized by an epistocratic council. This council could not make law, only "unmake" it, and would likely be composed of individuals who pass rigorous competency exams.[31]

Mechanisms of participatory democracy

[edit]Scholars have recently proposed several mechanisms to increase citizen participation in democratic systems. These methods intend to increase the agenda-setting and decision-making powers of the people by giving citizens more direct ways to contribute to politics.[33]

Citizens' assemblies

[edit]Also called mini-publics, citizens' assemblies are representative samples of a population that meet to create legislation or advise legislative bodies. When citizens are chosen to participate by stratified sampling, the assemblies are more representative of the population than elected legislatures.[34] Assemblies chosen by sortition provide average citizens with the opportunity to exercise substantive agenda-setting and/or decision-making power. Over the course of the assembly, citizens are helped by experts and discussion facilitators, and the results are either put to a referendum or sent in a report to the government.

Critics of citizens' assemblies have raised concerns about their perceived legitimacy. Political scientist Daan Jacobs finds that although the perceived legitimacy of assemblies is higher than that of system with no participation, but not any higher than that of any system involving self-selection.[35] Regardless, the use of citizens' assemblies has grown throughout the early 21st century and they have were often used in constitutional reforms, such as in British Columbia's Citizens' Assembly on Electoral Reform in 2004 and the Irish Constitutional Convention in 2012.[36]

Deliberative opinion polls

[edit]

Trademarked by Stanford professor James S. Fishkin, deliberative opinion polls allow citizens to develop informed opinions before voting through deliberation. Deliberative polling begins with surveying a random representative sample of citizens to gauge their opinion.[37] The same individuals are then invited to deliberate for a weekend in the presence of political leaders, experts, and moderators. At the end, the group is surveyed again, and the final opinions are taken to be the conclusion the public would have reached if they had the opportunity to engage with the issue more deeply.[37] Philosopher Cristina Lafont, a critic of deliberative opinion polling argues that the "filtered" (informed) opinion reached at the end of a poll is too far removed from the opinion of the citizenry, delegitimizing the actions based on them.[38]

Public consultation surveys

[edit]Public consultation surveys are surveys on policy proposals or positions that have been put forward by legislators, government officials, or other policy leader. The entirety of the deliberative process takes place within the survey. For each issue, respondents are provided relevant briefing materials, and arguments for and against various proposals. Respondents then provide their final recommendation. Public consultation surveys are primarily done with large representative samples, usually several thousand nationally and several hundred in subnational jurisdictions. .

Public consultation surveys have been used since the 1990s in the US. The American Talks Issue Foundation led by Alan Kay played a pioneering role.[39] The largest such program is the Program for Public Consultation at the University of Maryland's School of Public Policy, directed by Steven Kull, conducting public consultation surveys on the national level, as well as in states and congressional districts. They have gathered public opinion data on over 300 policy proposals that have been put forward by Members of Congress and the Executive Branch, in a variety of areas.[40] Such surveys conducted in particular Congressional districts have also been used as the basis for face-to-face forums in congressional districts, in which survey participants and House Congressional Representative discuss the policy proposals and the results of the survey.[41]

The questionnaires used in the surveys by the Program for Public Consultation, which they call “policymaking simulations”, have also been made available for public use, as educational and advocacy tools.[42] Members of the public can take the policymaking simulations to better understand the proposal, and are given the option to send their policy recommendations to their elected officials in Congress.

E-democracy

[edit]E-democracy is an umbrella term describing a variety of proposals to increase participation through technology.[43] Open discussion forums provide citizens the opportunity to debate policy online while facilitators guide discussion. These forums usually serve agenda-setting purposes or are sometimes used to provide legislators with additional testimony. Closed forums may be used to discuss more sensitive information: in the United Kingdom, one was used to enable domestic violence survivors to testify to the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Domestic Violence and Abuse while preserving their anonymity.

Another e-democratic mechanism is online deliberative polling, a system in which citizens deliberate with peers virtually before answering a poll. The results of deliberative opinion polls are more likely to reflect the considered judgments of the people and encourage increased citizen awareness of civic issues.[43]

Liquid democracy

[edit]In a hybrid between direct and representative democracy, liquid democracy permits individuals to either vote on issues themselves or to select issue-competent delegates to vote on their behalf.[44] Political scientists Christian Blum and Christina Isabel Zuber suggest that liquid democracy has the potential to improve a legislature's performance through bringing together delegates with a greater awareness on a specific issue, taking advantage of knowledge within the population. To make liquid democracy more deliberative, a trustee model of delegation may be implemented, in which the delegates vote after deliberation with other representatives.

Some concerns have been raised about the implementation of liquid democracy. Blum and Zuber, for example, find that it produces two classes of voters: individuals with one vote and delegates with two or more.[44] They also worry that policies produced in issue-specific legislatures will lack cohesiveness. Liquid democracy is utilized by Pirate Parties for intra-party decision-making.

Participatory budgeting

[edit]Participatory budgeting allows citizens to make decisions on the allocation of a public budget.[45] Originating in Porto Alegre, Brazil, the general procedure involves the creation of a concrete financial plan that then serves as a recommendation to elected representatives. Neighbourhoods are given the authority to design budgets for the greater region and local proposals are brought to elected regional forums. This system lead to a decrease in clientelism and corruption and an increase in participation, particularly amongst marginalized and poorer residents. Theorist Graham Smith observes that participatory budgeting still has some barriers to entry for the poorest members of the population.[46]

Referendums

[edit]In binding referendums, citizens vote on laws and/or constitutional amendments proposed by a legislative body.[47] Referendums afford citizens greater decision-making power by giving them the ultimate decision, and they may also use referendums for agenda-setting if they are allowed to draft proposals to be put to referendums in efforts called popular initiatives. Compulsory voting can further increase participation. Political theorist Hélène Landemore raises the concern that referendums may fail to be sufficiently deliberative as people are unable to engage in discussions and debates that would enhance their decision-making abilities.[34]

Switzerland currently uses a rigorous system of referendums, under which all laws the legislature proposes go to referendums. Swiss citizens may also start popular initiatives, a process in which citizens put forward a constitutional amendment or propose the removal of an existing provision. Any proposal must receive the signature of 100,000 citizens to go to a ballot.[48]

Town meetings

[edit]In local participatory democracy, town meetings provide all residents with legislative power.[45] Practiced in the United States, particularly in New England, since the 17th century, they assure that local policy decisions are made directly by the public. Local democracy is often seen as the first step towards a participatory system.[49] Theorist Graham Smith, however, notes the limited impact of town meetings that cannot lead to action on national issues. He also suggests that town meetings are not representative as they disproportionately represent individuals with free time, including the elderly and the affluent.

See also

[edit]- Citizens' assembly

- Civic intelligence

- Collaborative governance

- Deliberative democracy

- Demarchy

- Direct democracy

- Green politics

- Inclusive Democracy

- Open source governance

- Participatory action research

- Participatory culture

- Participatory budgeting

- Participatory justice

- Public incubator

- Public participation

- Public sphere

- Radical transparency

- Sociocracy

- Sortition

- Workers' council

Notes

[edit]- ^ "Definition of participatory democracy | Dictionary.com". www.dictionary.com. Retrieved 14 May 2022.

- ^ "Participatory Democracy". Metropolis. Retrieved 14 May 2022.

- ^ "democracy | Definition, History, Meaning, Types, Examples, & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 15 May 2022.

- ^ Tanguiane, Andranick S. (2020). Analytical theory of democracy : history, mathematics and applications. Cham, Switzerland. ISBN 978-3-030-39691-6. OCLC 1148205874.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ US EPA, OITA (24 February 2014). "Public Participation Guide: Introduction to Public Participation". www.epa.gov. Retrieved 15 May 2022.

- ^ a b De Vos et al (2014) South African Constitutional Law – In Context: Oxford University Press

- ^ a b c d Wolfe, Joel D. (July 1985). "A Defense of Participatory Democracy". The Review of Politics. 47 (3): 370–389. doi:10.1017/S0034670500036925. ISSN 1748-6858. S2CID 144872105.

- ^ a b c Pateman, Carole (March 2012). "Participatory Democracy Revisited". Perspectives on Politics. 10 (1): 7–19. doi:10.1017/S1537592711004877. ISSN 1541-0986. S2CID 145534893.

- ^ Democracy : the unfinished journey, 508 BC to AD 1993. John Dunn. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 1992. ISBN 0-19-827378-9. OCLC 25548427.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b Raaflaub, Kurt A. (2007). Origins of democracy in ancient Greece. Josiah Ober, Robert W. Wallace. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-93217-3. OCLC 1298205866.

- ^ Theoharis, Athan (July 1994). "The Age of McCarthyism: A Brief History with Documents". History: Reviews of New Books. 23 (1): 8. doi:10.1080/03612759.1994.9950860. ISSN 0361-2759.

- ^ "The Early State, Its Alternatives and Analogues". www.socionauki.ru. Retrieved 14 May 2022.

- ^ Davies, John K. (15 March 2004), "1 Athenian Citizenship: The Descent Group and the Alternatives", Athenian Democracy, Edinburgh University Press, pp. 18–39, doi:10.1515/9781474471985-007, ISBN 9781474471985, S2CID 246507014, retrieved 14 May 2022

- ^ "Women and Family in Athenian Law". www.stoa.org. Retrieved 14 May 2022.

- ^ a b Ross 2011, Chapter 4. The Importance of Meeting People

- ^ Fishkin 2011, passim, see especially the preface.

- ^ "We the Citizens Speak Up for Ireland -- Final Report" (PDF). December 2011.

- ^ a b Giraudet, Louis-Gaëtan; Apouey, Bénédicte; Arab, Hazem; Baeckelandt, Simon; Begout, Philippe; Berghmans, Nicolas; Blanc, Nathalie; Boulin, Jean-Yves; Buge, Eric; Courant, Dimitri; Dahan, Amy (26 January 2021). "Deliberating on Climate Action: Insights from the French Citizens' Convention for Climate". S2CID 234368593.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Wilson, Claire Mellier, Rich. "Getting Climate Citizens' Assemblies Right". Carnegie Europe. Retrieved 12 March 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Krutka, Daniel G.; Carpenter, Jeffery P. (November 2017). "DIGITAL CITIZENSHIP in the Curriculum: Educators Can Support Strong Visions of Citizenship by Teaching with and about Social Media". Educational Leadership. 75: 50–55 – via EBSCOhost.

- ^ Won, No (April 2017). "Ideation in an Online Participatory Platform: Towards Conceptual Framework". Information Polity. 22 (2–3): 101–116. doi:10.3233/IP-170417.

- ^ Mattson, Gary A. (Spring 2017). "Democracy Reinvented: Participatory Budgeting and Civic Innovation in America". Political Science Quarterly. 132: 192–194. doi:10.1002/polq.12603.

- ^ James Miller (25 October 2011). "Will Extremists Hijack Occupy Wall Street?". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 29 October 2011. Retrieved 21 November 2011.

- ^ A Defense of Participatory Democracy, Joel D. Wolfe, The Review of Politics 47 (3): 370–389.

- ^ Plotke, David (1997). "Representation is Democracy". Constellations. 4 (1): 19–34. doi:10.1111/1467-8675.00033. ISSN 1467-8675.

- ^ a b "Don't be fooled by citizens' assemblies". Unherd. 26 July 2019. Retrieved 24 July 2021.

- ^ Fuller, Roslyn (4 November 2019). In Defence of Democracy. Polity Books. ISBN 9781509533138.

- ^ "The digital age has sparked anxiety about democracy". Catholic Herald. 5 March 2020. Retrieved 24 July 2021.

- ^ Fuller, Roslyn (15 November 2015). Beasts and Gods: How Democracy Changed its Meaning and Lost its Purpose. Zed Books. ISBN 9781783605422.

- ^ Fuller, Roslyn. "SDI Digital Democracy Report". Solonian Democracy Institute. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- ^ a b Jason., Brennan (26 September 2017). Against democracy. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-17849-3. OCLC 1041586995.

- ^ Illing, Sean (23 July 2018). "Epistocracy: a political theorist's case for letting only the informed vote". Vox. Retrieved 16 April 2021.

- ^ Landemore, Hélène (2020). Open democracy : reinventing popular rule for the twenty-first century. Princeton, New Jersey. ISBN 978-0-691-20872-5. OCLC 1158505904.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b "6. The Principles of Open Democracy", Open Democracy, Princeton University Press, pp. 128–151, 31 December 2020, doi:10.1515/9780691208725-008, ISBN 978-0-691-20872-5, S2CID 240959282, retrieved 17 March 2021

- ^ Jacobs, Daan; Kaufmann, Wesley (2 January 2021). "The right kind of participation? The effect of a deliberative mini-public on the perceived legitimacy of public decision-making". Public Management Review. 23 (1): 91–111. doi:10.1080/14719037.2019.1668468. ISSN 1471-9037. S2CID 203263724.

- ^ Van Reybrouck, David (17 April 2018). Against elections : the case for democracy. Seven Stories Press. ISBN 978-1-60980-810-5. OCLC 1029788565.

- ^ a b "What is Deliberative Polling®?". CDD. Retrieved 23 April 2021.

- ^ Lafont, Cristina (March 2015). "Deliberation, Participation, and Democratic Legitimacy: Should Deliberative Mini-publics Shape Public Policy?: Deliberation, Participation & Democratic Legitimacy". Journal of Political Philosophy. 23 (1): 40–63. doi:10.1111/jopp.12031.

- ^ Kay, Alan F. (1993). "One Small Step for Democracy's Future: A New Kind of Survey Research". The Newsletter of PEGS. 3 (3): 13–20. ISSN 2157-2968. JSTOR 20710628.

- ^ "PPC Survey Archives | Program for Public Consultation". Retrieved 20 October 2023.

- ^ Gaines, Danielle E. (12 September 2023). "In effort to improve public policy, simulations put everyday people in policymakers' shoes". Maryland Matters. Retrieved 20 October 2023.

- ^ "Policymaking Simulations –". Retrieved 20 October 2023.

- ^ a b Smith, Graham (2009). Democratic innovations : designing institutions for citizen participation. Cambridge, UK. ISBN 978-0-511-65116-8. OCLC 667034253.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Blum, Christian; Zuber, Christina Isabel (2016). "Liquid Democracy: Potentials, Problems, and Perspectives". Journal of Political Philosophy. 24 (2): 162–182. doi:10.1111/jopp.12065. ISSN 1467-9760.

- ^ a b Smith, Graham (2009), "Studying democratic innovations: an analytical framework", Democratic Innovations, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 8–29, doi:10.1017/cbo9780511609848.002, ISBN 978-0-511-60984-8, retrieved 18 March 2021

- ^ Novy, Andreas; Leubolt, Bernhard (1 October 2005). "Participatory Budgeting in Porto Alegre: Social Innovation and the Dialectical Relationship of State and Civil Society". Urban Studies. 42 (11): 2023–2036. Bibcode:2005UrbSt..42.2023N. doi:10.1080/00420980500279828. ISSN 0042-0980. S2CID 143202031.

- ^ Chollet, Antoine (2018). "Referendums Are True Democratic Devices". Swiss Political Science Review. 24 (3): 342–347. doi:10.1111/spsr.12322. ISSN 1662-6370. S2CID 158390740.

- ^ Linder, Wolf; Mueller, Sean (2021). Swiss Democracy. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-63266-3. ISBN 978-3-030-63265-6. S2CID 242894728.

- ^ Frank., Bryan (2010). Real Democracy : the New England Town Meeting and How It Works. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-1-282-53829-0. OCLC 746883510.

References

[edit]- James S. Fishkin (2011). When the People Speak. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-960443-2.

- Carne Ross (2011). The Leaderless Revolution: How Ordinary People Can Take Power and Change Politics in the 21st Century. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-84737-534-6.

Further reading

[edit]- Baiocchi, Gianpaolo (2005). Militants and Citizens: The Politics of Participatory Democracy in Porto Alegre. Stanford University Press.